Marie Curie, an outstanding scientist and feminist

A Life Dedicated to Science and Research

Marie Curie, born Maria Salomea Skłodowska on November 7, 1867, in Warsaw, grew up in a well-educated Polish family marked by personal tragedy, including the deaths of her sister Zofia (1876) and her mother Bronisława (1878). Her father, Władysław Skłodowski, a physics teacher, transmitted to her a deep scientific culture within a politically tense context: Poland was under Russian domination, and the intellectual elite maintained a strong national consciousness.

In Warsaw, Maria attended clandestine courses at the Flying University, the only institution that allowed women to receive advanced higher education. She also worked as a governess to finance her scientific studies. Her path was characterized by discipline, intellectual rigor, and a constant desire for progress.

In 1891, she moved to Paris and enrolled at the Sorbonne. University records confirm her outstanding achievements: a degree in physics in 1893 and another in mathematics in 1894. During this period, she met Pierre Curie, an established physicist introduced to her by Józef Wierusz-Kowalski. Their intellectual compatibility quickly led to scientific collaboration and, in 1895, to marriage.

From 1897 onward, the couple focused on studying the uranium rays identified by Henri Becquerel. Their experimental work relied on precise measurements using the piezoelectric electrometer developed by Pierre and his brother Jacques. After processing and purifying tons of pitchblende, they isolated two new elements: polonium (named in homage to Poland) and radium in 1898.

In 1903, Henri Becquerel, Pierre, and Marie Curie were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for their pioneering work on radioactivity. Documents from the Nobel Committee confirm that Pierre insisted that Marie’s essential contribution be officially recognized.

Pierre Curie’s accidental death in Paris in 1906 marked a turning point. Marie succeeded him at the Sorbonne, becoming the first woman to teach there. She continued their research alone and received the 1911 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the isolation of pure radium and the study of its properties.

That same year, the press revealed her private relationship with Paul Langevin. Newspapers exploited the affair in a climate of xenophobia and suspicion toward a foreign woman in a leading scientific position. Press archives from 1911 reflect the hostility she faced. Marie Curie refused to justify herself publicly and focused exclusively on her research.

During World War I, she organized a network of mobile radiology units—known as the “Little Curies”—to locate shrapnel in wounded soldiers. Military health service records estimate that several hundred thousand radiological examinations were made possible thanks to her initiative. Her daughter Irène, then 17, actively took part in the operations.

After the war, Marie Curie became director of the Radium Institute, inaugurated in 1918. The institute quickly became a major international center for radioactivity research, welcoming scientists such as André Debierne and later Frédéric Joliot. Irène Curie, trained there, received the 1935 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with her husband for the discovery of artificial radioactivity.

Marie Curie also took part in the Solvay Conferences, gatherings of the world’s most prominent physicists, including Einstein, Planck, Lorentz, and Rutherford. Albert Einstein’s letters reveal his constant admiration for her scientific rigor and his condemnation of the personal attacks she faced.

Marie Curie died in 1934 from aplastic anemia, likely caused by years of unprotected exposure to radioactive sources. In 1995, Pierre and Marie Curie were interred in the Panthéon in Paris, in recognition of their monumental contribution to science. Both had refused the Legion of Honor.

Pierre Curie and Piezoelectricity

Pierre Curie and his brother Jacques Curie discovered piezoelectricity in 1880: certain crystals generate an electric charge when subjected to mechanical stress. This discovery led to the development of the piezoelectric electrometer, an essential measuring instrument used extensively by Marie Curie in her research on radioactivity. Its use is documented in technical publications from 1898 to 1904.

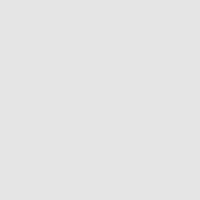

Unique Bookends for the Curie Museum

Since 2020, we have collaborated with the Curie Museum (Muzeum Marii Skłodowskiej-Curie) in Warsaw with our Pierre and Marie Curie bookend set.

The two physicists are depicted working in their laboratory. Pierre Curie stands with a document in hand beside an electroscope of his own design. Marie Curie sits at her worktable with a piezoelectric electrometer, also developed by Pierre, used to measure the electric charge produced by radioactive emissions. This instrument, originally inspired by studies from physicist Gabriel Lippmann, became central to the Curie couple’s groundbreaking research on radioactivity.

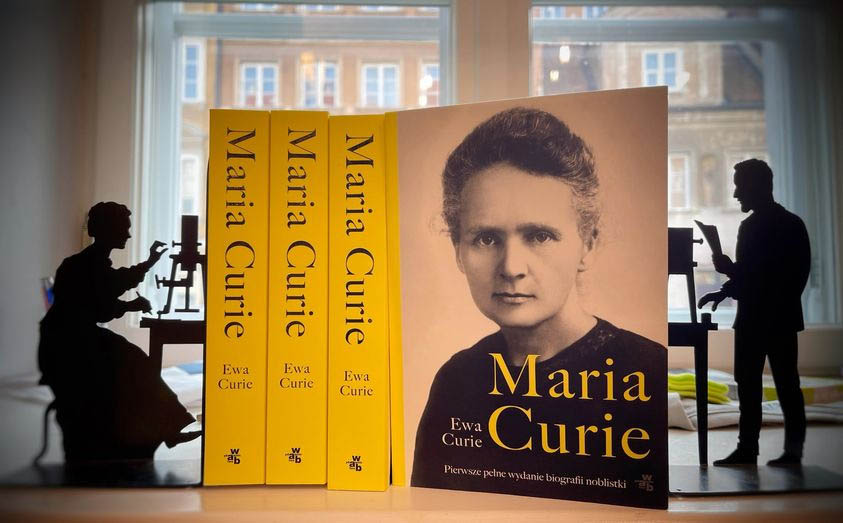

Marie Curie is particularly appreciated by Japanese visitors.

Add elegance and science to your home library with our Pierre & Marie Curie bookends

Enhance your bookshelves with our Pierre and Marie Curie bookends. These unique pieces protect your books while transforming your library into a tribute to scientific history. Perfect for creating an elegant reading corner or surprising someone with a thoughtful, decorative, and memorable gift.

Useful links – Pierre & Marie Curie

Pierre & Marie Curie – Science & Legacy

Maria Skłodowska – Childhood, Studies & Scientific Formation